Americans from coast to coast treasure our national monuments, parks, and forests. Given the overwhelming popularity of these lands today, it is often forgotten that for over 100 years conservation critics have tried to block nearly every attempt to protect public lands for future generations. From the very earliest days of American conservation, a vocal minority has remained opposed to any and all new land protection measures.

Thankfully, America’s great conservation leaders had the foresight and courage to protect our nation’s iconic lands in the face of intense hostility from pro-development and anti-conservation interests. If our national leaders of yesterday had heeded the demands of these conservation opponents, some of our most breathtaking landscapes—from Acadia to the Grand Canyon and from Canyonlands to California’s redwoods—would have remained unprotected and open to the pressures of development and privatization.

In the second half of the 19th century—before the birth of the Antiquities Act in 1906—commercial interests coalesced against efforts to protect what is perhaps the nation’s most iconic national park: mining prospectors, cattle grazers, and railroads all eyeing tracts of land in the Grand Canyon. In 1897, an Arizona newspaper called the campaign to protect the landscape a “fiendish and diabolical scheme,” saying that the fate of the state depended “exclusively” on mineral extraction.

Efforts to protect the Grand Canyon repeatedly failed in Congress as legislators bent to the will of shortsighted opposition efforts. It wasn’t until 1908, after Congress again refused to preserve the landscape as a national park, that President Theodore Roosevelt stepped in to permanently protect the Grand Canyon as a national monument. Using the Antiquities Act, then just two years old, Roosevelt set aside what he called an “absolutely unparalleled… natural wonder” for future generations. The Grand Canyon would spend over a decade as a national monument before being designated a national park in 1919.

Today, Grand Canyon National Park draws 5.5 million visitors, creating nearly 9,000 local jobs and injecting over $800 million into the economy. A “fiendish and diabolical scheme” indeed.

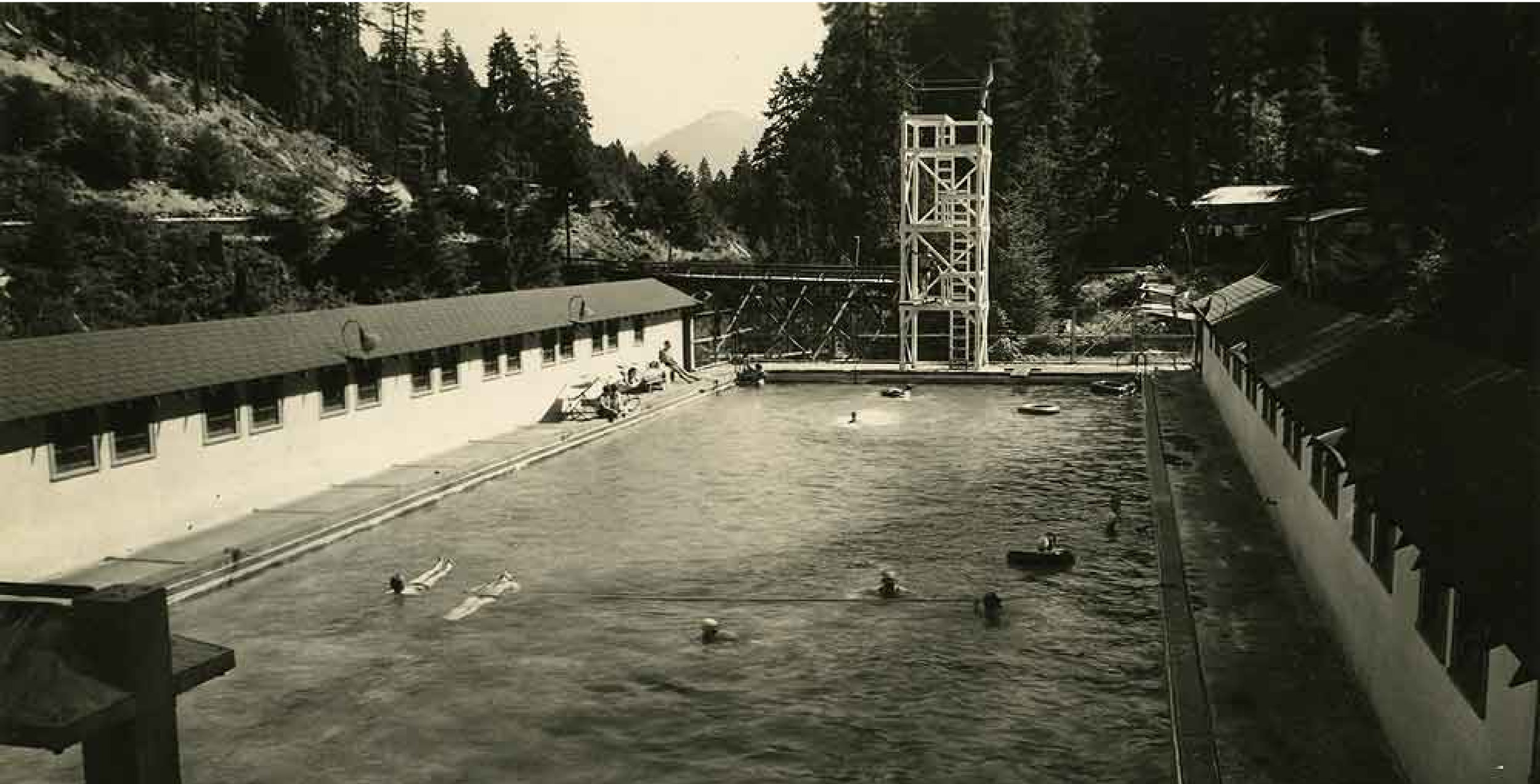

Again and again, vocal opponents to proposed conservation measures continue to march out the same tired predictions: Yellowstone National Park was to be a “great blow” to Montana communities; Olympic National Park in the Pacific Northwest, the work of “foolish sentimentalists;” Alaska’s Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, a “monstrous crime.” Even Utah’s Canyonlands, one of the state’s “Mighty 5” national parks, was predicted to “forever stunt” the area’s growth.

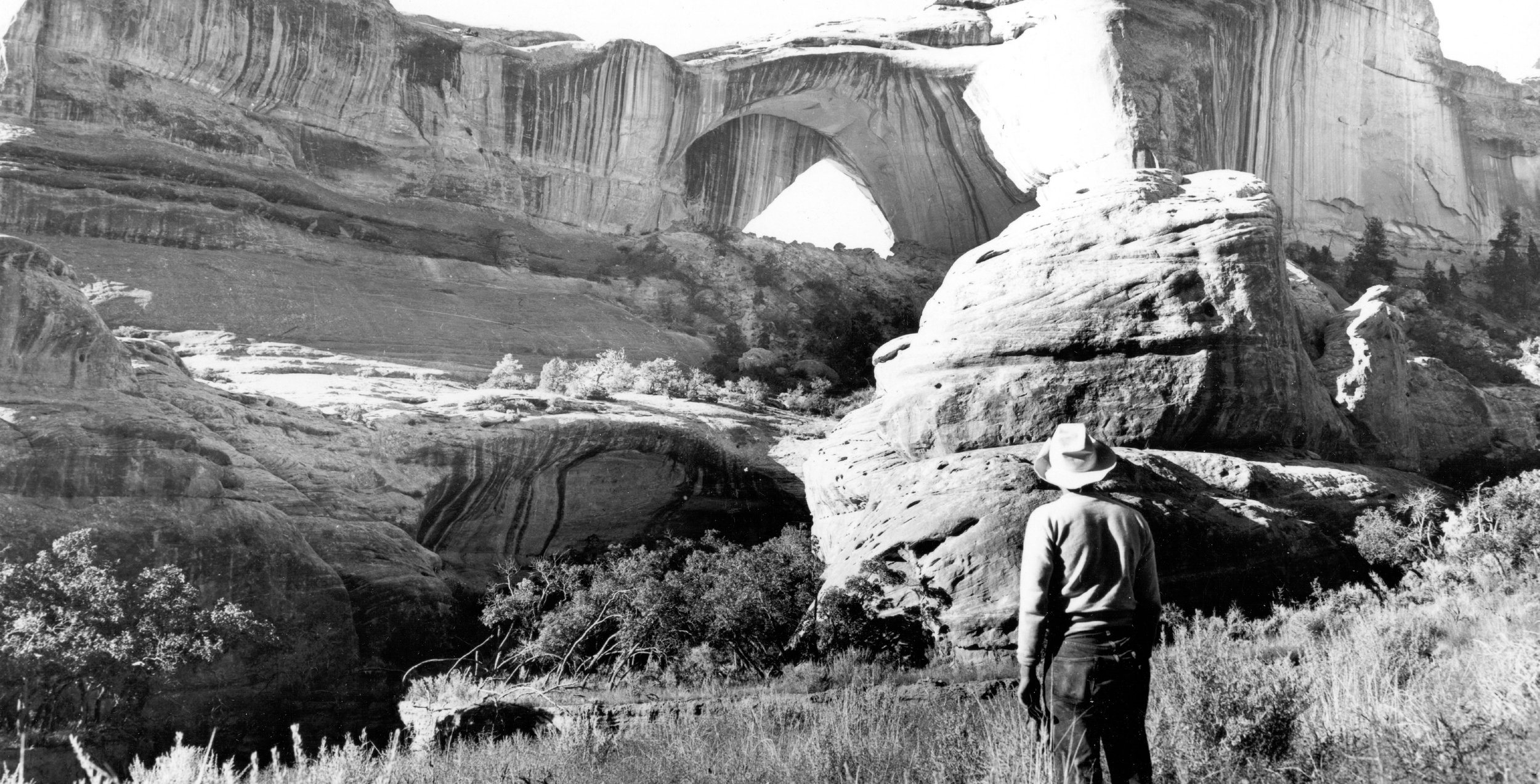

Today, the ideological arguments made against land protections are virtually identical to those made in past decades as leaders worked to protect some of America’s most iconic parks and monuments. The proposal to permanently protect the Bears Ears region—named for its stunning twin plateaus in southeastern Utah—was met with the same kind of opposition that the Grand Canyon saw in 1897. Some politicians, like San Juan County Commissioner Bruce Adams, echoed opponents from centuries past, contending that a designation would damage the economy, despite a century’s worth of evidence to the contrary.

After being sidelined in the Utah public lands planning process, the region’s nearby tribes unveiled a proposal to protect this spectacular landscape of steep cliffs and winding canyons as a national monument. In 2016, their hard work paid off when President Obama designated Bears Ears National Monument.

Now Bears Ears is under attack again, with Utah’s own leadership asking President Trump to erase the national monument and threatening to withhold management funding.

Now isn’t the time drag out the same tired maxims—that conservation will “stifle,” “ban,” and “stunt” local economic activities—but to support our national monuments and ensure they are protected for generations to come.